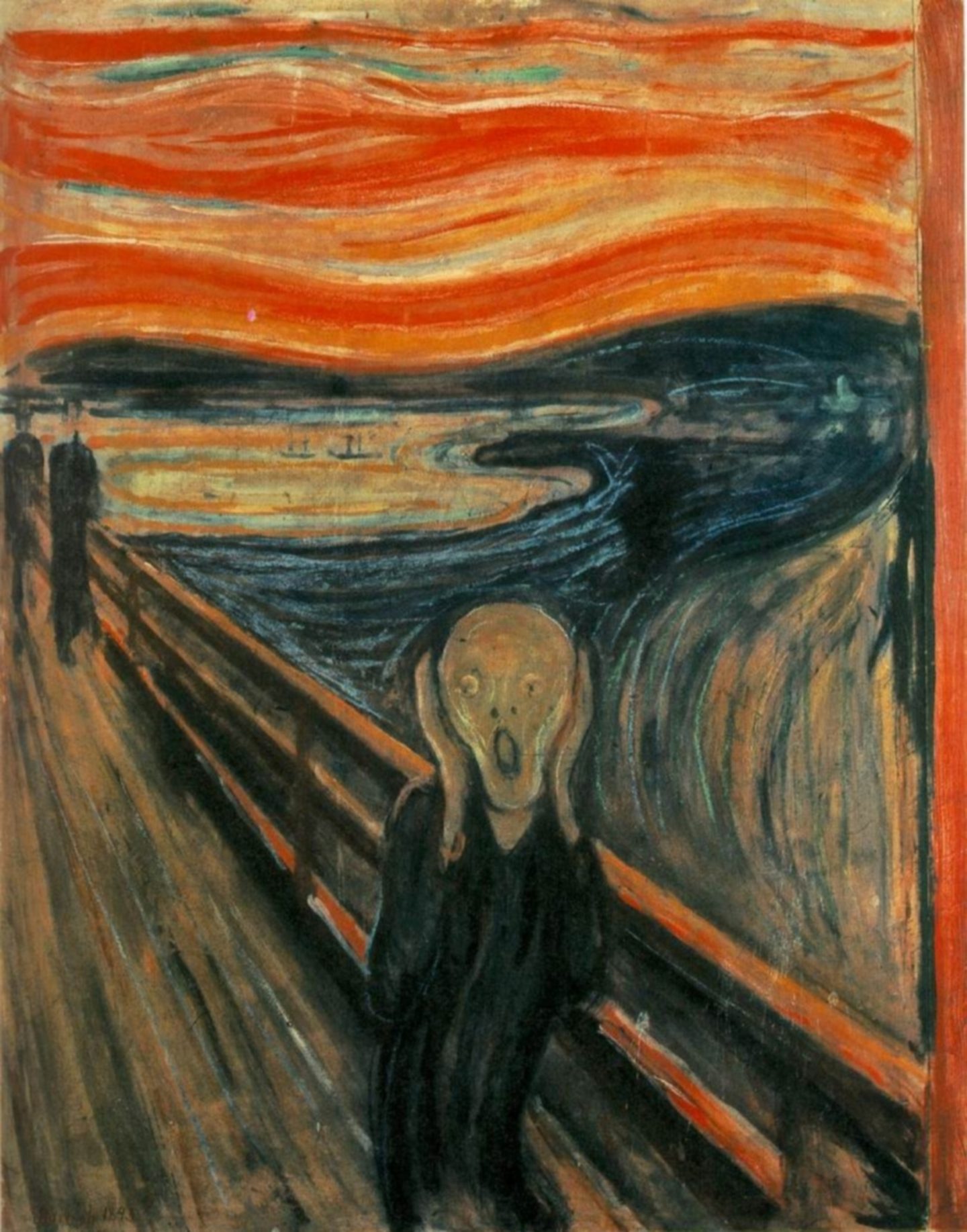

They say that there is madness behind every artist. And one who comes to mind is Edvard Munch, a Norwegian painter whose most iconic work is “The Scream”. What is perhaps fascinating about “The Scream” is that it captures the feeling of alienation and anxiety so well, the terrifying and lonely figure juxtaposed between a landscape of normalcy and insanity.

Our modern world is filled with mad and anxious people. According to Statistics Canada, 23.0% of Canadians aged 15 and older (6.7 million people) reported that most days were ‘quite a bit’ or ‘extremely stressful’ and about 1 in 5 Canadians will experience mental illness in some form. My fellow science colleagues can surely attest to this.

The balancing act of juggling a full course load and the pressures of high performance, working part-time jobs, participating in extracurricular activities, (the list goes on) leaves little time to do anything else – like sleeping – even though sleeping less than 5 hours a day has been shown to decrease immune function, increase the build-up of beta amyloids in the brain, reduce cognitive function and memory, and a multitude of other effects.

Is there any weed for a weed like me? I’m stressed…. 🙁 (Photo by user FoeNyx under the GNU Free Documentation License)

Students or even humans aren’t the only ones however. Plants, microbes and fungi experience stress too, but for us, that’s a good thing. When their innate immune response is triggered by stressors such as toxins or pollutants, secondary metabolites are produced which are essential to their adaptive defense mechanisms in changing environments – a phenomenon known as hormesis. These secondary metabolites can be harnessed by humans for their immuno-stimulatory or anti-inflammatory effects, a property which is currently being investigated by some of your very own profs at UNBC!

But, as always, there is a caveat. Stress is what keeps us alive. It increases our arousal and keeps us motivated to do something, anything – rather than getting bored. In fact, would you rather inflict pain on yourself rather than be bored? The answer is surprising. You probably would.

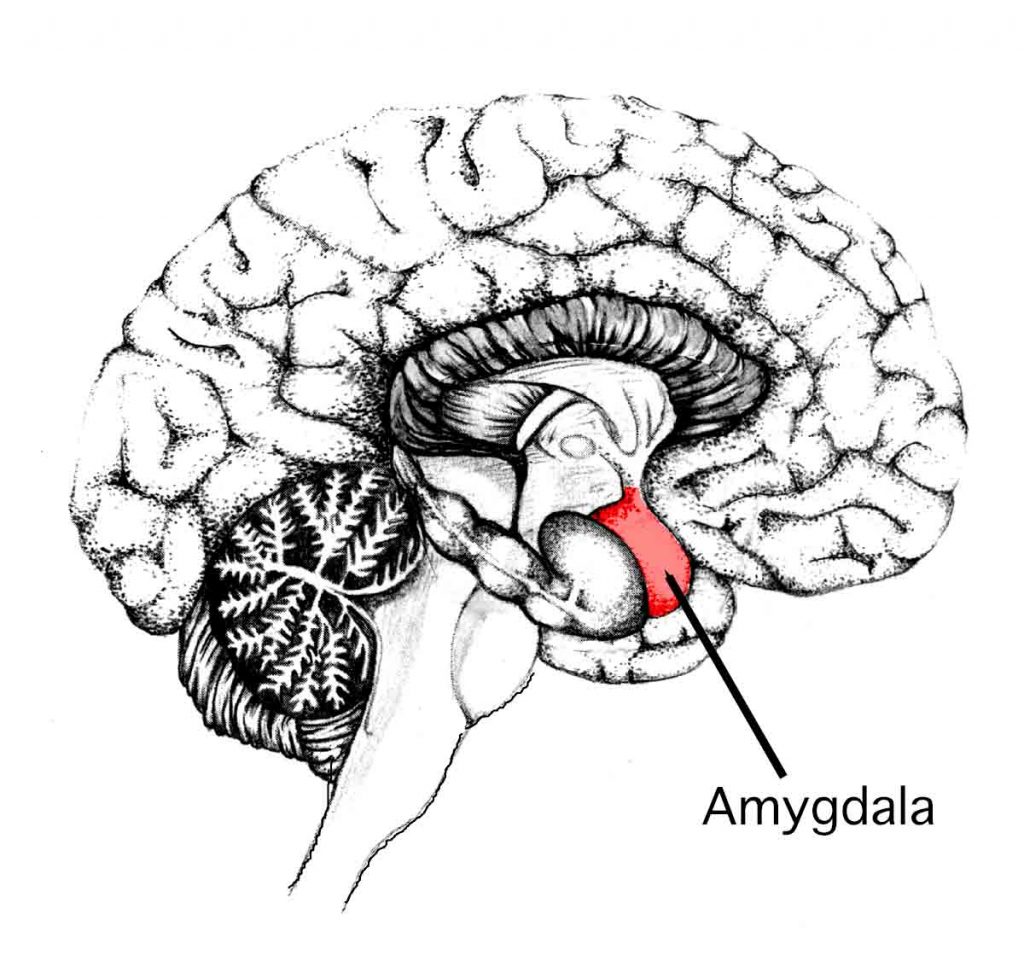

Aside from this, stress is what makes humans highly adaptable to dangerous and life-threatening situations. There is a famous story of a sole plane crash survivor named Juliane Koepcke who lived through 10 days in the forest without food while sustaining several serious injuries, including an arm that was infested with maggots. When faced with danger or fear, our amydala, the “fear centre” of our brain is activated and adrenaline is released manifesting in “superhuman” powers which only arise during these “do or die” scenarios.

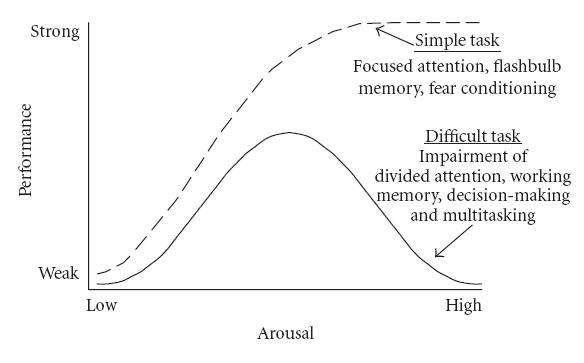

The Yerkes-Dodson Model (Image under Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication originally from Yerkes and Dodson 1908)The psychological Yerkes Dodson model is a good indicator that shows to what extent stress can improve our performance and motivate us to achieve our goals, but what happens when we pass that threshold?

If you don’t have the amygdala, you won’t experience fear or stress… but it also means you’ll probably die. (Image under Creative Commons CC0 1.0 Universal Public Domain Dedication from user Sgerstenberg)

Stress has many physiological effects on the body; scraps from our primitive past when our primary concern was whether we could outrun a bear rather than worry about being late for work. More specifically, it activates the flight or flight response via our sympathetic system, releasing hormones such as cortisol and epinephrine that present numerous effects on the body. This is great in the short term. If chronic however, it can cause many harmful symptoms such as weight gain, hypertension, mental illness and yes, even death. In Japan, the prevalence of death from overworking has even led to the development of its own word – Karoshi.

The intersectionality between our mind and how it can influence our physiology is best encapsulated by the emerging field of psychoneuroimmunology. This discipline places emphasis on how our subjective behavioural experiences of stress can be extrapolated to a weakened immune system leading to tumorigenesis, disease, and can even affect cancer survivorship. In addition, it explains how those who experience mental health issues are much more likely to participate in health-harming activities such as smoking, drugs and alcohol consumption because they are less likely to “care”. Therefore, it has become important to recognize the holistic health of the individual rather than treating the patient by their physical symptoms alone. This is a key concept in the placebo effect, a powerful yet underestimated factor in our health.

However, stress is a very subjective experience. Not everyone thinks diving off a cliff is stressful or getting a 50% on a midterm is particularly life-threatening. For daredevils, people who thrive on perilous encounters, being in a constant state of stress is like a drug to them. Scientists who study these individuals have suggested both a genetic and environmental factor in how people perceive stressful situations. So, can we change the way we react to a stressor and can it help us with mental illness?

Historically, people who suffered from anxiety disorders and mental illness did not even see it as problem – a view which still persists in many developing countries. Though the stigma of mental illness has been lifted in our modern society, people are being diagnosed with mental illnesses more now than ever before, (some misdiagnosed) with the treatment in the form of prescription drugs to manage their problems – a typification shared with type II diabetes. Not only does this place a huge financial burden on the Canadian healthcare system, but it also does little to fix the real cause. Students shouldn’t be taking pills because they are depressed from having no life outside of school, but the school system should change so that students aren’t depressed. A big difference. Additionally, there are many other conducive ways of coping with stress such as exercise, meditation, or painting.

Edvard Munch might be crazy… but I least he’s crazy with style.(Photo under Creative Commons 2.0 Generic License)

If there is anything that I have learned from looking at “The Scream”, from an artist who in our time would be diagnosed with psychosis and bipolar disorder, it is that stress and succumbing to it doesn’t make us weak or feeble. If anything, Munch’s depiction of himself staring at us with his mouth agape from anguish and panic provides us with a glimpse of reality, humanity, and compassion. So this exam season, thank Stress for making you study, but if you need to… scream it out. It’s healthy.

Recent Comments