Art and Science are like two sides to the same coin. They attempt to explain the unexplainable, and to make the explainable understood. Often, the coherence of a painting, a play, or a scientific phenomenon is not discovered until we grow older and become more retrospective and experienced. As a non-sentient embryo, the future probably doesn’t exist yet, as a child, the future appears so long and distant that it is a trivial consideration, while as an adult, the past is nostalgic, and time becomes ever so precious. Our narratives depend on our perception of time, and our place in it changes as we age.

What is the Meaning of Life? I don’t even have one… I’m a student.

Photo from: CollegeDegrees360 on Flickr

Attribution – ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0)

It is from this unique awareness of time and our experiences in the context of our physical world which kickstarts our ontological quest for meaning. This was the reason I identified with Shakespeare’s Hamlet when I first read it as a teenager, because the questions he asked resonated with my attempt to find the answers to why we existed. Ironically though, this fixation on life, death and existence was so overbearing that it would eventually lead to his end and it eventually distracts us from what is really important – the time we have left.

Death is a universal affliction, and if we are fortunate enough not to be killed violently, such as by an unexpected car collision, then there is one statistically inevitable fate that all must succumb to, and that is death from the consequence of aging and disease.

But what does it mean to be dead or alive? Does our obsession and fascination with zombies stem inherently from our interest in understanding whether our memories and consciousness constitutes a primary component of one’s identity? Do people in comas experience pain and are they as good as “dead”? Could we use the same justification for embryos that are used for stem cell research? One thing is for sure, no one wants to look like a zombie.

Yes, that’s right, I’m giving YOU the stink eye for that one!

Photo by Zoosnow licensed under CC0 Creative Commons

Indeed, people are so preoccupied with outward appearances that many have gone through great extremes to “appear” youthful. From a Countess who bathed in the blood of young virgins, to the ancient Greeks and Romans that applied crocodile dung as an aging remedy, and Victorian women who unwittingly used mercury to remove wrinkles by skin corrosion, people constantly seek ways to appear youthful and reverse the signs of aging. Even today, women are using skin care products made from placentas and blood facials and performing body enhancing surgeries to achieve this effect. New special “diets” designed to live healthier longer lives are touted in every website and social media website.

However to understand aging at its root cause, we’ll have to examine our smallest living constituents – our cells. Cells arise and die constantly in our bodies through the cell cycle.

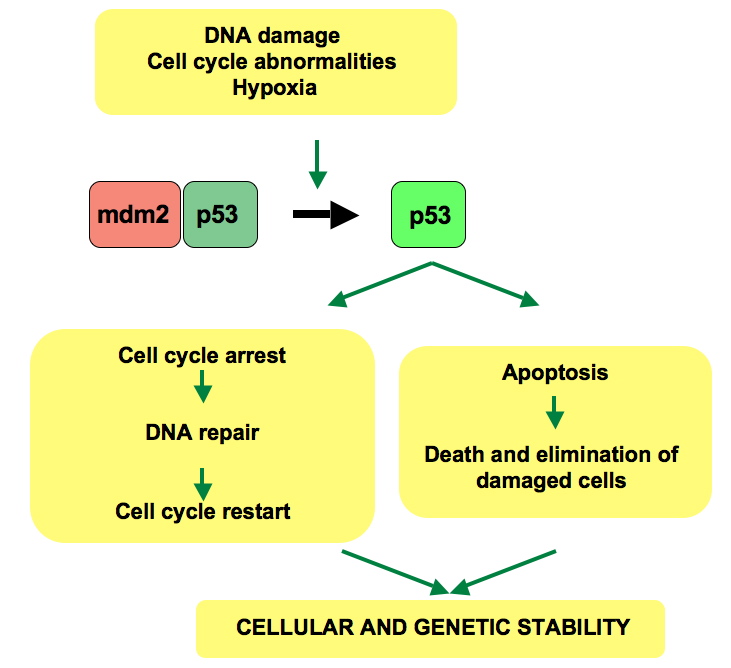

A protein integral in this modulation of the cell cycle is protein p53 which is implicated in half of all human cancers. P53 arrests damaged cells at the G1 checkpoint and also induces cell death through apoptosis. However, because p53 is a tumor suppressor and its mechanism activates cell death, it can also shorten a person’s lifespan considerably through uncontrolled apoptosis, thus a balance between the process of cell proliferation and death needs to be achieved.

p53 plays an important role in cell aging by causing apoptosis or cell cycle arrest

Photo from Thierry Sousi

Public Domain image

Still, other theories of aging attribute aging and disease to the generation of damaging free radical oxygen species, the build-up of insoluble metabolic by-products such as cholesterol containing plaques and B-amyloids in the brain, or from a lack of stem cell regeneration. Another popular theory is one involving telomeres, the protective caps at the ends of DNA chromosomes that are progressively shortened with every cell cycle. If there is a way to decrease the rate of telomere shortening, cell senescence could also be slowed, and our lives can be prolonged.

Perhaps there are already organisms that have solved this problem. The naked mole rat, for example, possesses a biological mechanism which prevents their cells from growing excessively, thereby bypassing cancer. Albeit, if looking like the naked mole rat is a prerequisite for anti-aging perhaps most people would probably pass.

This is what immortal looks like… having second thoughts about the whole anti-aging thing?

Photo from Jedimentat44 on Flickr, licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution 2.0 Generic license

But sometimes, the factors which could lead to a long life can extend beyond the biological. TIME has a life expectancy calculator which includes different parameters such as education and marital status. According to other scientists, there are many other underlying determinants to a long and healthy life. Factors such as social integration, diet and exercise all affect us at the biological level to protect us from cell damage.

Additionally, perhaps it is comforting to know that we never really truly die. According to the 1st law of thermodynamics, nothing really dies if the conventional definition of “death” entails the fact that we no longer exist. All the atoms that make up our body get transferred into another form, as Gertrude to Hamlet says quite eloquently, we are just “passing through nature to eternity”. And if not, we will be remembered by loved ones, and our actions forever impactful for those still living.

But what would happen if we were to live forever?

Would we choose to use that time to educate ourselves? To further improve humanity and alleviate suffering? Or would we use that time to be hedonistic and irresponsible? Could we “buy” more time? The controversy and ethics surrounding this issue make these questions hard to resolve for years to come.

Wait I can live forever? I can finally win this game! Just one more turn… WORLD DOMINATION here I come!

Photo from Yongho Kim on Flickr

Attribution – ShareAlike 2.0 Generic (CC BY-SA 2.0)

For now, it seems the best way to confront aging is to accept that it is simply a fact of life, and knowing so, we should be living in the present moment, preoccupying ourselves with activities which makes our lives meaningful for as long as we have. It might be tomorrow, or it might be 20 years from now, we’ll never know. The beautiful thing about aging? Is that we do have some control over it.

Because even though “To be or not to be” is the question, the more important one is what we can choose to be once we are.

Recent Comments