Breaking news, everyone: Suicide can be a bad thing. But not for the reasons you are thinking of.

Allow me to explain. In this case, when we say “suicide” we’re talking about the programmed death of individual cells of an organism, a phenomenon known as apoptosis. Perhaps it seems counter-intuitive to us that organisms would benefit from cells dying, but there are actually many reasons why a cell would apoptose— for example, if they are diseased, for developmental reasons, or to just generally to get rid of cells that are no longer needed. It should be mentioned that apoptosis is not just a messy explosion of cellular parts (like necrosis, which is uncontrolled cell death), but rather a systematic and well-regulated process that includes cell shrinkage, nuclear collapse, and DNA condensation and fragmentation; notably, the process concludes with macrophages on clean-up duty, engulfing the cell debris. Cell death is just a part of life, paradoxically enough, and therefore you can see why cell “suicide” can actually be expected to be beneficial.

Apoptosis vs. Necrosis. Image credit: National Institute on Alcohol Abuse and Alcoholism CC-PD.

However, it can be exploited. This is seen in the case of many viruses that infect a multicellular organism. Generally, viruses propagate by inserting their genetic material into host cells and co-opting the cell’s machinery to replicate its own genes and coat proteins. Some viruses will insert their genome into the cell’s DNA and allow the cell to replicate (lysogenic cycle), and along with it replicating its own DNA, until some trigger such as UV light causes virus production (entering the lytic cycle).

Lytic Cycle vs Lysogenic Cycle. Image credit: Suly12 CC BY-SA 3.0

So, how does the virus life cycle relate to apoptosis? As noted earlier, apoptosis is often used to get rid of diseased cells— infected cells “commit suicide” for the good of the whole organism, making it a defense against viruses. However, some viruses have the ability to repress apoptosis using proteins that bind to the cell’s apoptotic factors— at least, until the viruses are ready to burst from the cell and spread, at which point it becomes convenient to have the host put up the Jolly Roger, so to speak.

Some viruses, such as the common flu, actually trigger apoptosis in their host cells in order to allow their progeny to spread to other cells. As mentioned earlier, apoptosis is a structured process. It doesn’t just blow up like Mount Vesuvius— the dying cell’s parts are compartmentalized into membrane bound vesicles and can be taken up by other cells. Some viruses can exploit this function in order to remain undetected by the immune system. While cellular contents are being packaged, viral particles sneak into these vesicles as well, and when released from the cell, remain unrecognized by immune cells. Therefore, those seemingly benign vesicles can fuse with the membranes of new cells, releasing the contents— including the viral ones— into a brand new host (talk about a Trojan Horse!). Thus, the cycle propagates right under the nose of the watchful immune system, and this is part of the reason why viruses can be so difficult to fight. Smart way to use your own strengths against you, huh?

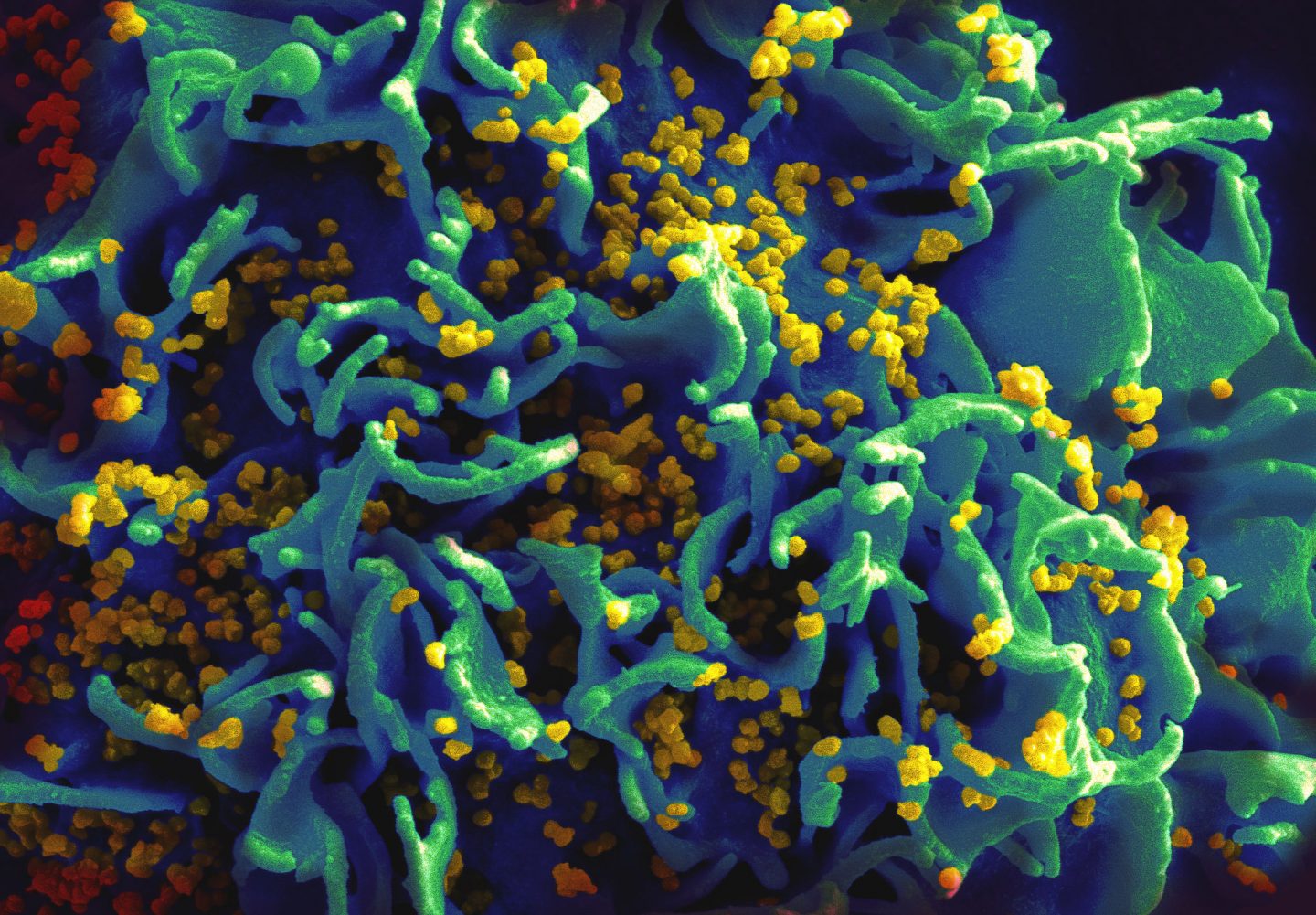

Let me just interject in the middle of all this and say it should be noted that virus-induced apoptosis doesn’t always work the same way. Viruses are diverse! And often, even within the same virus, we see different relationships to apoptosis. To demonstrate the complexity of all this, let’s examine the case of Human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV), a disease I am sure you have totally never heard of in your entire life. The virus weakens the immune system by killing off immune cells, leaving us vulnerable. There are many mechanisms proposed for how it might do this, and evidence for many of those proposals as well; so there might just be more than one way. For one, it kills immune system cells by using secreted proteins to force the cell to express “suicide genes”. One paper proposes the involvement of the Fas ligand, which is a normal ligand that, when binding to its receptor on the cell, induces apoptosis; the authors found that HIV-positive patients exhibit higher levels of expression of this ligand than normal, as well as higher sensitivity to it in their T cells. These authors also proposed that cell death is caused by HIV activating certain signalling proteins that would start HIV production in the cell but also inadvertently trigger apoptosis. In that case, cell death is simply a side-effect of the virus trying to reproduce, but also happens to work in its favour.

But wait! That’s not all. HIV can also induce apoptosis in T cells that it has not yet infected, something we might call a bystander effect. Nardelli et al. noted that uninfected blood lymphocytes cultured together with infected ones died as well, and their research led them to believe that secreted viral proteins can induce apoptosis in other cells (as an aside, this brings up an interesting question to me— why would the virus kill nearby cells it could potentially use as host in the future? I couldn’t find an answer.). And this is just the tip of the iceberg, so it becomes easy to see why HIV, and viruses like it, can be such a formidable enemy to beat.

To summarize: Some viruses try to stop apoptosis (“Don’t die because I need you.”). Some viruses cause apoptosis (“Die, I don’t need you anymore but I do need a way out of this cell.”). Some viruses try to reproduce and end up causing apoptosis along the way (“I’m just going to co-opt some of your cellular machinery for a moment— whoops, I didn’t realize that button would also make you die?!”). Some viruses cause apoptosis in neighbouring cells (“Everyone else can die too because I’m full of spite.”). The diversity of these mechanisms goes on and on, as do my bad jokes, but you can begin to see from this discussion why viruses are so effective. As the main takeaway here, hopefully I have provided some insight into how and why viruses may use a cell’s built-in suicide mechanism against them.

Another takeaway: next time you have the flu, entertain yourself between sneezes by remembering that the virus is forcing you to destroy yourself slowly from the inside, cell by cell! But don’t be too alarmed, because your body does that naturally too. Sounds like a fun dinner time conversation, doesn’t it? Ah, science. You really kill me.

Recent Comments